Unpopular Opinion #3: Your Kid Most Likely Won’t Play a D1 Sport in College and Clubs Know That

Youth sports have become a multi-billion dollar industry. Maybe that is a problem.

Of course, we all like to believe that our kid will be the next Patrick Mahomes, LeBron James, Caitlin Clark, or Alex Morgan. Statistically, the odds are stacked waaaaaaay against that happening. Nonetheless, generation-after-generation of parents firmly believe their kids will be among the select few who play college sports, with far too many thinking that activity will occur at a Division I (D1) program. Every year, competitive sports club prey on these parents to extract billions of dollars out of them knowing that the majority won’t make it to college teams and the few that do will do so at the D2, D3, or NAIA level and receive athletic scholarships below what the parents spent on club fees, uniforms, equipment, gasoline, hotels, food, airfare, camps, and private lessons over the years. I knew one family who could barely afford all of these costs, but sacrificed because they were sure their daughter would play at a major D1 program. She ended up at a D3 school with a weak academic reputation. Imagine the pressure kids must feel to perform knowing what their parents are sacrificing on their behalf. That is a lot of mental health pressure.

In most cases, their kids are coached by men and women far too obsessed with winning then molding young boys and girls into strong leaders. My middle kid played competitive soccer for years, including at the olympic development level. She received an early college offer, but was so burned out by the terrible coaching she had tolerated for years that she decided to stop player soccer. Through all her years of soccer, she had one coach for half a season who was excellent, but he left mid-season to coach in college. The rest were pretty awful. My oldest daughter spent time in competitive club volleyball and went through the same coaching hell. The worst by far was a female coach who I believe was emotionally abusive to the group of 13-year-old girls. She wrecked my daughter’s self-esteem by benching her for roughly 90% of matches over the course of weekend matches—weekend-after-weekend. After pleading with the club to drop her to a more appropriate team and being rebuffed, we removed her from the club. We didn’t have ego or delusions about her playing in college. We just didn’t want her being treated so harshly as a young teenager still growing into her body and mind. She eventually returned to volleyball at a different club and for her high school and enjoyed playing again thankfully—she even played club at her college.

In total, I estimate we spent over $50,000 on competitive sports clubs for the kids, as well as countless hours driving to and from practices and tournaments as far as Missouri and North Carolina. Had I known before we started what I know now, I would have never put my kids through these experiences, including dealing with the cut-throat parents who saw everything as a zero-sum game. We all know parents who “red-shirted” their kindergartners so they’d be the oldest kids in their high school classes, with the hope they’d have physical advantages on the field. I remember one parent spent an entire tryout in her car with binoculars to grab the tryout numbers of every kid so she would know who made which team the moment the lists were released. If not for the memories I got to make with my kids during the down time outside of the games and practices, the money and time would have been totally wasted.

When it comes to youth sports, most people don’t appreciate that kids mature at different rates. That means that a faster and earlier maturing kid might stand out at U14, but by U18 the other kids may have caught up to and surpassed her. I remember one young girl on the top volleyball team at U14 who was leagues above most of the other players. She was a joy to watch. By U18, however, she had stopped growing as the other girls kept growing, resulting in them passing her by and her being dropped to a lower team. You see the same thing happen when it comes to Five-Star football recruits. At 18-years-old, these young men are bigger, stronger, and faster than other young men because in many cases they matured earlier. By the time they hit their junior or senior years of college, many other young men have caught and surpassed them.

Now, by 18-years-old, most young players have finished growing, so being a Five-Star football recruit is better than not being one by that age. It just doesn’t mean those players will continue to dominate and have strong careers in college or in the National Football League (NFL). As the article below notes, many of the NFL's biggest stars weren’t Five-Star college recruits.

Roughly 30 players earn the gilded five-star status each year. This year, there were 32. Another 200 or so players are graded as four-star prospects. Hundreds more are three stars.

…

The NFL’s showcase event annually serves as a reminder of the inexact science of evaluating and projecting high school football players. When you’re dealing with living, breathing people, things change. Players mature. They evolve and develop. Sometimes rapidly.

Some of the Chiefs' and 49ers' biggest stars — such as Patrick Mahomes, Deebo Samuel, Travis Kelce and George Kittle — were relatively unheralded high school players. Christian McCaffrey was the one big-time prospect among them, and even he was ranked in the bottom of the top 100 in his class. The others were relative nobodies and garden variety two- and three-star prospects.

Statistically, as one study showed, “[c]oming out of high school, a 5-star recruit thus has a 39 percent chance of "sticking" in the league. Three of every five will not.”

A far better gauge of whether kids will play sports in college and at the D1 level is the athletic success of their parents. Genes matter. A lot. You see it professionally fairly often. Take McCaffrey. His dad, Ed, was a star receiver at Stanford followed by the Denver Broncos. His mom, Lisa, was a star soccer player at Stanford. Lisa’s dad, Dave Sime, was an Olympian. McCaffrey’s three brothers all played or play at D1 programs. Or take the amazing NBA basketball player Steph Curry. His dad, Dell, played in the NBA, as does his brother, Seth, and his mom. Sonya, played volleyball at D1 Virginia Tech. Curry’s younger sister, Sydel, played volleyball at D1 Elon University. Based on anecdotal evidence gathered over my twenty-plus years of coaching youth sports, I know genetics matter a great deal. My buddy played at a D1 college. Two of his three kids are also D1 athletes, with the third still in high school. A few others guys played D1 and professional sports. Their kids ended up at D1 schools, too. I could go on. If you doubt me, read David Epstein’s book, “The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance,” which contains great stories about how great genes routinely beat 10,000-hours of practice.

Regardless, I believe we’ve got the whole athletic-academic priorities thing out-of-whack.

I can’t tell you how many times I entered a club’s training facility decked out with college banners of the places where some of the club’s graduates went to play college sports. The same goes for most of the kids signing letters of intent on Signing Day or in social media posts letting everyone knew where they “plan to pursue my athletic career.” The vast majority of those colleges were D2, D3, or NAIA schools I never heard of, with inferior athletic facilities and even worse academic records. Because most were private schools, I can only imagine how much their parents paid in tuition, room, and board for their kid to play college sports at Never Heard Of U., as the scholarship money likely wasn’t much.

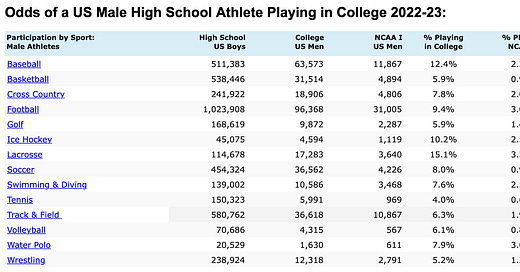

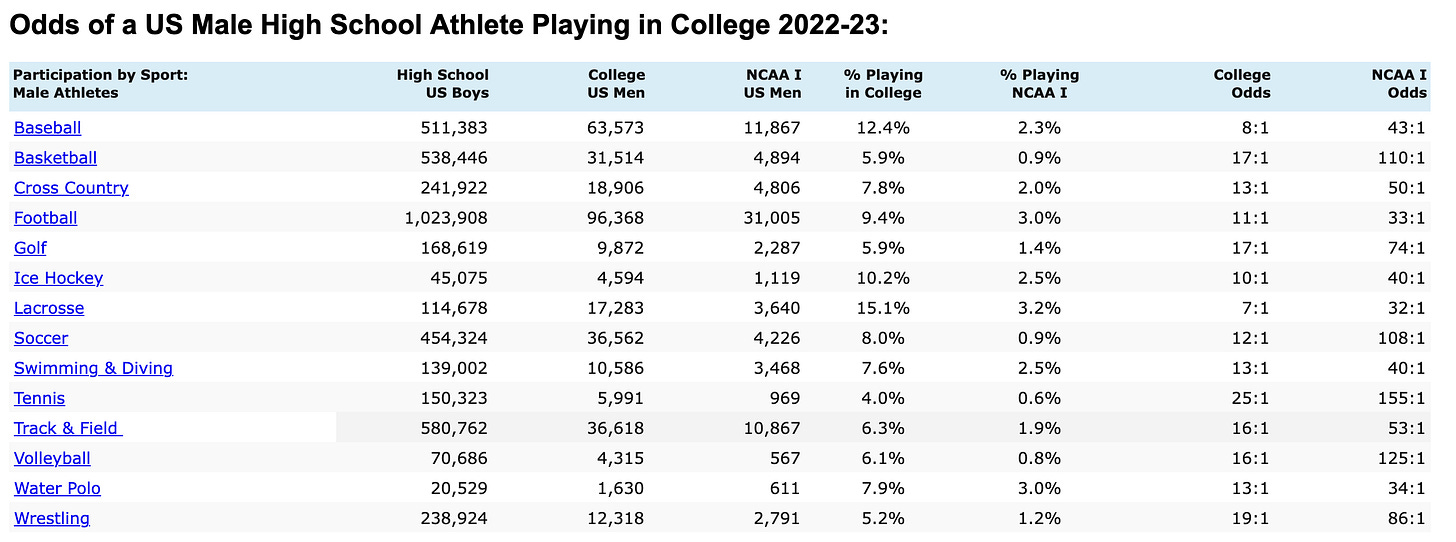

Let’s look at three examples. At the high school level, 463,328 girls play volleyball. Of those girls, just under 34,000 (7.3%) will play in college, with just 5,543 (1.2%) making it to a D1 school. The average value of an athletic scholarship for playing volleyball in college is just $31,138, or $7,784.50 per year. Girls basketball produces similar numbers. In boy’s basketball, the numbers are even worse. From 538,446 high school players, just over 36,000 end up playing in collage, with a mere 4,895 (0.9%) making it to a D1 program. The average value of an athletic scholarship for playing basketball in college is just $38,246, or $9,561.50 per year. Of the 1,023,908 boys who play football in high school, only 31,005 (3.0%) will earn D1 status, which comes with an average value of $36,070, or $9,017.50 per year. That is not a lot of money compared to what parents spend in order for those players to reach the collegiate level. Moreover, all of those collegiate athletes dedicate countless hours during their college years engaged in their sports. If we divide all of the money they get by the hours spent engaged in their sports, my guess is the per hour rate is below minimum wage. The advent of the NIL era will change that dynamic for some players, but not for most.

I think we need to flip the script, especially when it comes to DI sports outside of football and basketball and all non-DI sports. Instead of having Signing Day for athletics, we should have Signing Day for academics. Why do we place so much emphasis on some kid going to Never Heard Of U. to play softball or lacrosse, with an athletic scholarship amounting to hardly anything? The degree from that unknown school won’t carry much weight in the real world when that kid is applying for jobs, as she will be competing against kids from more impressive academic schools. There is a strong argument to be made that the kid would have been better off in the long term going to a better academic school and not playing sports (or just playing club) than playing sports at an unknown and weak academic school. The family I mentioned above, like many families, would have been better off investing all of the money spent on sports in a 529 plan so their daughter could have gone to a better academic school, thereby launching her career for the long term.

In contrast, why do we place so little emphasis on the kid getting a full or substantial academic scholarship to an elite or well-known school? High school is or should be about the academic success of the kids. The athletics should be focused on supplementing their academics and teaching them valuable skills on leadership, teamwork, grit, and resiliency. Yet, we fail to shine a spotlight on the academic successes as we do the athletic successes. Walk into any high school. You’ll likely see pictures of the kids who were named All-State athletically, but will struggle to find the wall with pictures of the kids who excelled academically. My kids’ high school recently rightly celebrated the professional success of sprint superstar Abby Steiner, but they never celebrate the success of the graduate who started a wildly successful company or hit the tops of their industries. This prioritization needs to change.

Some will disagree with me, but it is far better for a kid to get a merit-based scholarship than an athletic scholarship. Why? The academic money paid is for PAST success that only requires meeting a fairly easy minimum Grade Point Average (GPA) going forward. Conversely, the athletic money paid is for FUTURE work in the form of playing a sport. It, too, comes with minimum GPA requirements, but it also comes with rigorous schedules for practice, weight training, study tables, games both on and off season, and the always present risk of serious injury. Lots of kids do a great job of balancing academics and athletics so excel at both simultaneously, but many kids can’t. Too often those kids emphasize their athletics over their academics, with the payoff never coming or being far less than they expected. It would be better for those kids to put more time in their studies and less into their sports, as the former will provide them with lifelong success as the latter may only carry them through high school or a non-D1 sport in a academically weak college, which will make it more difficult for those kids to compete for jobs after leaving college.

To deal with clubs taking advantage of parents and their players who likely don’t know the stats shown above, Ohio should require all competitive sports programs charging more than $500 to participate to annually publish data on what their graduates did after high school. The data should include the number of players graduating, the number who signed letters of intent to play in college, the breakdown on the divisional status (D1, D2, D3, or NAIA) of those colleges, the U.S. News & World Report academic rankings of those colleges, and the average athletic scholarships awarded to their players. This data would allow parents and their players to evaluate clubs to make the decision on whether investing in competitive club sports is worth taking. Without such data, clubs can mislead parents and their players about the overall success of their clubs at getting their players into D1 programs with large scholarships.

Youth sports have become a multi-billion dollar industry. Maybe that is a problem.

I think you should truly consider a run for governor!!!

Another great article, Matt! I can relate to your parent comments. Thank goodness my son knew that he did not want to play the games swimming would require and he focused on the academic rewards, friendships, and graduating in four years without debt.

Young parents would do well reading and digesting your information to avoid getting caught up in the sports' running here, there, and every where, etc.