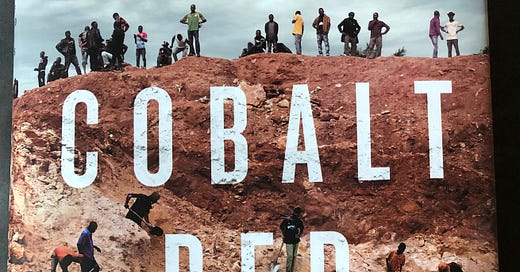

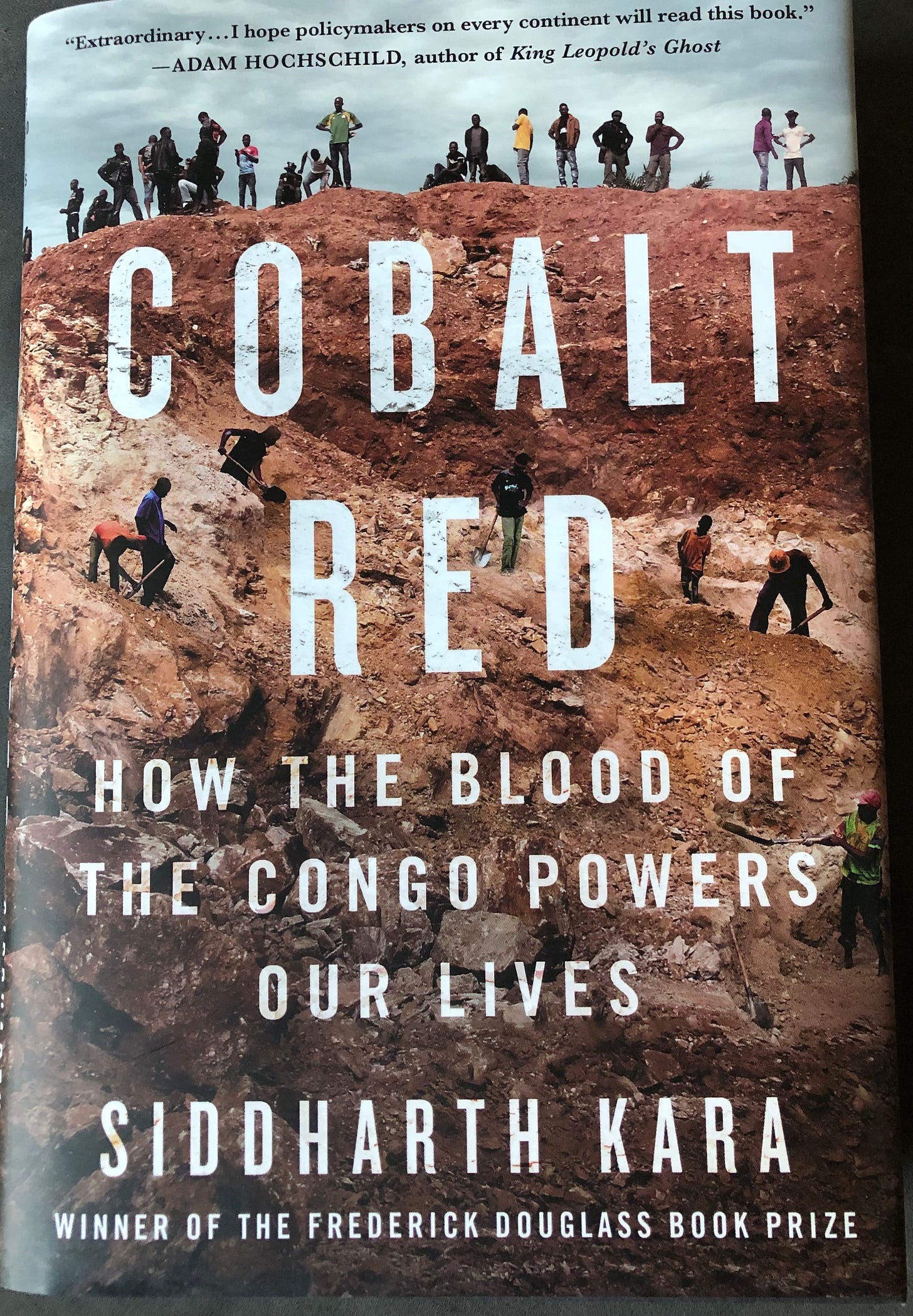

Book Review: Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the DRC Powers Our Lives by Siddharth Kara

The virtue signaling smugness of EV drivers should come to an end.

“We would not send the children of Cupertino to scrounge for cobalt in toxic pits, so why is it permissible to send the children of the DRC?”

“We would not treat our hometowns like toxic dumping grounds, so why do we allow it in the DRC?”

There are books that move our hearts like Victor Hugo’s “Les Miserables.” Then there are books that move our minds. Siddharth Kara’s “Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the DRC Powers Our Lives” is one of those mind-moving books. Kara spent several years in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) inspecting mines, interviewing laborers, and exploring the system the provides the developed world with the cobalt it desperately needs for rechargeable batteries. “Cobalt Red” exposes in gory detail how the batteries in our smartphones, electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, and solar panels more often than not contain cobalt mined by the slave labor of children, with many of those children grossly underpaid, physically abused, poisoned by toxic chemicals daily, and, in too many cases, killed in the collapsed cobalt tunnels throughout the DRC.

If those politicians, corporations, and consumers living blissfully in the developed world driving their Teslas read Kara’s eye-opening book, the zealous push for more EVs, wind turbines, and solar panels and the cobalt-sucking batteries those items must have would rapidly slow. What good does a world adhering to The Paris Agreement do for a child in the DRC whose life involves little more than spending ten hours a day dangerously digging for cobalt? What good do lower coastlines in America or Europe do for a child choked by filthy, polluted air, land, and water and surrounded by environmental destruction on a heretofore unimagined scale? I’m pretty sure those children eagerly would trade a slightly hotter world for even the slightest chance at a childhood and a marginally cleaner country.

Just wait until they realize their African continent must stay deprived of natural gas or nuclear energy that would make their lives substantially easier because wealthy westerners who already harnessed fossil fuels to the extreme now believe a few extra degrees increase must be stopped. No matter that plants and trees actually prefer more carbon, which creates a greener world.

At any rate, Kara does an excellent job not only detailing the devastation wrought by our need for cobalt, but ties how the pillaging of the DRC today is not much different from the pillaging that has occurred in the DRC during the slave trade and the rubber boom. The west has been raping the DRC for centuries. Kara sees little hope that the pillaging will end any time soon.

Kara also eviscerates any claim the end-users of cobalt like Tesla and Apple can say that the cobalt THEY use is “clean” cobalt that only comes from industrial mining. In mine after mine, Kara shows how the artisanal mining output (i.e., cobalt mined by slave child labor) is mixed with the industrial mining output at the mines or fairly soon thereafter. By the time the cobalt is put in our smartphones, EVs, wind turbines, and solar panels, the certainty that every battery contains child slave labor cobalt is rock solid.

The heart-wrenching stories Kara tells about the children he comes across are shocking and, at times, unbelievable. From a rape surviving 15-year-old girl dying of AIDS with an emaciated baby strung to her back (he discovers both have died on his final trip to the DRC) to boy-after-boy whose legs are useless, mangled appendages in need of medical care crushed by tons of rocks in collapsing tunnels (they were “lucky” to be close to the opening so got dug out in time unlike the dozens of boys permanently buried in the rock), I cannot imagine how Kara slept at night knowing there was nothing he could do to help these innocent victims other than gather their stories and write his book.

I challenge anyone to read Kara’s book without feeling guilty about the cobalt we all use every day in our computers, smartphones, and, for some, EVs, as well as in wind turbines and solar panels. I’d like to think that my habit of using small rechargeable devices for years lessens the need for cobalt and that such cobalt could be harvested the right way—that the problem really is the massive amount of cobalt each EV, wind turbine, or solar panel battery needs that is truly driving the madness in the DRC and other places digging for the large amounts of lithium, cooper, and other precious metals needed in batteries, chargers, wind turbines, and solar panels of the “green” energy movement.

The greatest tragedy is that all of the horribles detailed in Kara’s book are largely unnecessary. The world could easily meet its energy needs by clean burning natural gas, which we have in abundance, and nuclear power, which is the cleanest energy we can harness. Plus, the carbon emissions from internal combustion engines (ICE) are, frankly, minimal in the grand scheme of carbon emissions, with studies showing that the end-to-end carbon footprint of a Tesla is similar to an ICE car. Those costs don’t, of course, include the physical, emotional, and mental harm done to the slave child laborer used in “green” energy, nor does it include the hundreds or thousands of children killed annually in the mining process.

“Cobalt Red” needs to be read by those advocating for EVs, wind turbines, and solar panels, so they know the true costs of what they are proposing. They should know the EV they are driving came on the backs of 10-year-old kids in Africa. The virtue signaling smugness of EV drivers should come to an end. Given that “green” energy is truly a first world “problem,” we can and should do better and be smarter, especially when it comes to the most vulnerable global population: children.